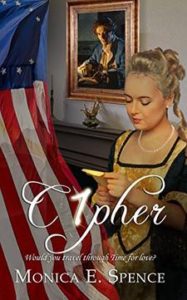

This essay is based upon my Author’s notes from my historical Romance novel, C1PHER, which is available as an ebook from Amazon, Barnes and Noble and from the publisher, The Wild Rose Press.

C1PHER is a work of historical fiction, with the tale carefully straddling history and storytelling, but there are times that truth is stranger than fiction. Writing Historical Fiction is like making a fresh loaf of bread. Kneading facts into the story mix must be leavened with a healthy dose of imagination. If there is too much fact or fiction, it becomes something else: fantasy, alternate history, biography, creative non-fiction, etc.

The story begins for me in 1978, when I moved into a house located directly across the street from the Raynham Hall Museum in Oyster Bay, Long Island, New York, about thirty miles east of Manhattan. Over the years I never forgot my fascination with, and my visits to, the old house.

Originally, the property of six acres ran from the shoreline of Oyster Bay to the hill where Lieutenant Colonel John Graves Simcoe later rebuilt an old fort with the stolen wood from the trees of the prized Townsend apple orchard. The property included a four room house and was purchased in 1738 by Robert’s father, Samuel Townsend. He expanded the home to eight rooms, calling it “the Homestead.”

In the 1850s, Samuel’s descendant, Solomon Townsend, again expanded and refurbished the house in the then-current Victorian style, complete with a tower, renaming it “Raynham Hall” after the ancient Norfolk, England seat of the Townsend family. History had come full circle. The house was deeded to the Daughters of the American Revolution in 1933. In 1941, the house was given outright to the DAR. In 1947 the DAR offered the house to the Town of Oyster Bay, and the Town restored the building to its Colonial proportions during the early 1950s. Raynham Hall has been recently restored again and open to the public, and the grounds include an Educational building.

Robert Townsend and Mary Banvard were actual people who lived in New York during the American Revolution.

Robert was born in Oyster Bay in 1753, the third child, and the third son, of eight children. Though nominally a Quaker (a member of the Society of Friends), he was the product of his parents’ influence— his father was a liberal (aka: political) Quaker and his mother, Sarah Stoddard, was an Episcopalian (Anglican). This background gave me the freedom to make Robert a man of a wider worldview.

Religious Quakers often used the archaic thee or thou in their speech, refused to use titles because they were in contradiction of the concept of equality of all people, which the Friends held so dear in their religious precepts. These Quakers wore plain clothing, rejected bright colors and adornment with lace, gold or silver, and they did not wear jewelry. Other Quakers, those of more liberal thought, saw no need to forgo the luxuries of life. Though a Quaker, Robert seemed to be a man who appreciated nice things, though he was neither ostentatious nor pretentious in his dress or his manner.

Quakers were sometimes slaveholders. Census records show that Samuel Townsend, Robert’s father, and the later Townsends at the Homestead, owned at least seventeen slaves between 1749 and 1795, who were housed in the Homestead’s attic. I do not know if Robert held slaves either in New York City, or when he moved back to Oyster Bay. I also have found no information as to whether or not Robert’s cousin, Peter Townsend, held slaves, but it worked in the storyline, so there it is. I apologize to him and his descendants if I have maligned his character by calling him a slaveholder.

The effort to end Quaker slaveholding began in the mid-seventeenth century. Eventually, those Quakers who remained slaveholders were given a choice: slaveholding or their religion. Most opted to free their slaves. In 1785, a delegation of freed slaves, led by the black abolitionist and former slave, Olauidah Equiano, thanked the Quakers for their efforts to stop slavery in the New World. With the inclusion of the characters of Dwayne, Tillie, and their sons, I wanted to show slavery in practice in Colonial America, even by Quakers, despite the practice was becoming very controversial in the Society of Friends by that time.

The Culper Gang was based on fact. (Many of you may be familiar with the Gang from the AMC television series TURN: Washington’s Spies.) Washington was desperate to get information from New York City, once the British took the city in 1776.

Robert Townsend was originally a pacifist but became influenced by another Quaker, Thomas Paine, whose pamphlet, Common Sense, spoke to the conflict of spirit Robert must have felt upon seeing the damage to his family’s property, the open flirting of the officers with his younger sisters, the loyalty oaths imposed upon the family, and the various insults suffered by his family while “hosting” Lieutenant Colonel Simcoe and his cohorts. Though Robert wished to help the Patriot cause, he could not become a combatant due to his Quaker beliefs.

Operating a dry goods business in the red-light district—ironically called “Holy Ground”—and working as a businessman and freelance journalist in British-occupied New York City, Robert was ideally situated to gather information for the leaders of the rebellious Colonial army. Beginning in June 1778, and working with several other native Long Islanders who were interrelated by friendship and family ties, Townsend passed his information in code, and/or invisible ink, to others in the chain, which eventually made its way to General Washington. It was the information discovered by Robert that revealed the truth about Major Andre, Benedict Arnold, and the plot to sell the fort at West Point to the British.

Toward the end of the war, Townsend made a special request of his handler, Colonel Benjamin Talmadge, to never reveal his identity either to Washington or the public. Spying was not considered respectable, no matter the importance of the cause. The secret of Culper Junior’s identity may never have been discovered, but fate intervened, as it so often does. In 1929, a request was made of Morton Pennypacker, a local state historian, to examine some papers discovered during a repair of Raynham Hall. A handwriting expert compared Robert Townsend’s handwriting with that of the more familiar hand of Culper, Jr., and Pennypacker realized Townsend and Culper were one and the same. He contacted a handwriting expert to confirm the findings. General George Washington’s most important spy, Samuel Culper, Junior, aka: Agent 723, was quiet, unassuming Robert Townsend.

On Mary Banvard there is considerably less information. She was not born of a noble or notable family, but instead, she was a Canadian-born housekeeper at Robert’s New York City apartment, which Robert shared with his brother William and another relative. Mary is attributed to be the mother of Robert’s natural son, Robert, Jr. Others believe William was the actual father of the child, but Robert accepted responsibility, gave the child his name, and paid for his schooling.

Another woman said to possibly be Robert Jr.’s mother was the mysterious female spy, Agent 355, who worked with Robert. Others say Agent 355 is simply the code book designation for a “Lady,” or a “woman of means,” as opposed to 701, an ordinary woman. After the Revolutionary War, somehow the stories about Townsend and 355 became conflated, suggested that a female agent 355 worked for Robert Townsend, bore his child, was arrested as a spy, and was confined, then died, on the British prison ship Jersey. A dramatic story, but questionable for many. So far we do not know the answer, which made the writing of my heroine, Mary, that much more fun.

My Mary is a highly educated, liberated, Twenty-first Century woman who made curiosity her sacrament. Her favorite question is why, and no matter what, she is strong enough to keep her feet moving forward, despite the odds. In the end gets her man and discovers some new things about herself.

In the story, Robert’s fiancée Mary was also strong, but she seems opinionated, narrow, unkind, selfish, and spoiled. I wanted to make the two Marys as opposite as I could. Of course, we are all hoping that twenty-first century Mary bonds with, and then falls in love with Robert, so they get their Happily-Ever-After (HEA).

Though we never meet her, I wonder what happened to Colonial Mary. Did she end up in the twenty-first century and find her own HEA? I hope she does.

One final note. The Townsend orchard eradicator and friend of Major John Andre, Lieutenant Colonel John Graves Simcoe, is said to be the author of the first American Valentine, which he gave to Sally (Sarah) Townsend, one of Robert’s sisters. No wonder Robert was so unhappy with the British camped out in the Homestead.

Though a brute in his iron-fisted control over Oyster Bay, and throughout his other postings in the American Colonies, Lieutenant Colonel Simcoe returned to England at the end of the War for Independence. He was a Member of Parliament and later appointed as the first Governor of Upper Canada. He founded the City of York (later: Toronto), abolished slavery in Upper Canada, and established the English traditions such as trial by jury. He is revered in Canada as a great patriot and in the United States he is remembered as a barbarian.

I hope you enjoy reading C1PHER as much as I enjoyed researching and writing it. I’m sad to say farewell to Mary and Robert for now, but there is always a possibility of another story.

Information on the history of Raynham Hall was based on the RaynhamHall Museum website (raynhamhallmuseum.org).